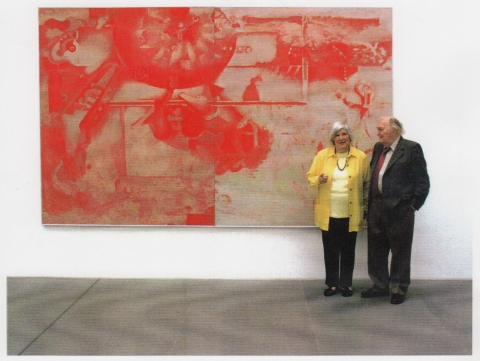

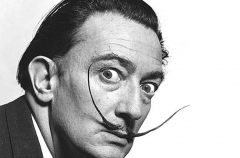

PHOTO: Karl Hagedorn and his wife Diana in front of one of the artist's paintings in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in Nuremberg, Germany.

INTRODUCTION

We met Karl Hagedorn in the 1990s when we were doing a show in New York. He came into our booth at the Pier Show, saw the kind of work we carried, and simply said, “I think you would like my work.” We did.

We started selling Karl’s work from the 1950s, including some work he had brought with him when he emigrated to the United States from Germany. Over time, we started selling his work from the 1970s, 1980s and beyond. It was a real joy knowing Karl, and it continues to be our joy selling his work and introducing him to new collectors.

His unique “Symbolic Abstraction” was celebrated and collected on both sides of the Atlantic, and still is today. Karl passed away in Philadelphia in 2005 from cancer. He painted right up until his last days. You can’t help but admire someone who, even knowing his days were numbered, was creating paintings with titles like “Celebration” and “Verve”.

Here, in his own words, is the story of his life. It is somewhat long, but worth reading.

Simply said, we think you will like his work.

Tony Fusco & Robert Four, Fusco & Four Modern

"THE STORY OF MY LIFE" - by Karl Hagedorn

In the 1920’s, I grew up in a small village in the Harz Mountains in the former Weimar Republic. Guentersberge had a population of 800 at the time and my grandfather was a respected architect there – what used to be called “a musischer mann.” My father, on the other hand, was all business, with a thriving sawmill nearby, which suddenly burst into flames one day – the most exciting day of my five-year-old life. The fire was glorious to me and my playmate cousin but an absolute disaster to everyone else. It flared and smoldered for an entire week, destroyed our house as well as the business, and led us to move to nearby Gernrode with what seemed like a huge population of 8,000. My father built a much larger sawmill and the fire became an always colorful but receding glow.

My childhood memories are full of remarkable machines. I particularly remember the big wheel of the huge steam engine that drove all of the machinery in the sawmill. A natural part of my everyday was made up of gears and all sorts of mechanical equipment, fine and coarse textures, grains of wood and a kaleidoscope of geometrical planes, more than enough to captivate and engross the eye of a child.

When I was not running up and down the mountains with the older boys or ice-skating and swimming in the many ponds, I would find a quiet spot and draw, something that gave me more and more pleasure and would remain so for a lifetime. At first I just drew objects around the house, in the sawmill and in the garden. I particularly remember when I was 7 or 8 drawing an old man on a stepladder picking apples from a tree and the feeling of satisfaction that I had got it just right. Drawing was more than mere objects after that.

One more thing stands out from my childhood --- the Romanesque church, the Cyriakus Kirche, a jewel from the 10th century that stood in the middle of Gernrode. Decades later I saw it reproduced in a textbook as an especially fine specimen of Romanesque art, but I always knew its unadorned simplicity, its stark architecture and geometrical forms not only appealed to me but represented an ideal of beauty that would stay with me always.

I was not a particularly good student and never really enjoyed my gymnasium years in Quedlinburg. But it was there that I discovered a subject of endless fascination, Durer, the mater draftsman: the precision, eloquence and range of his drawings. Throughout my high school years, to draw became also to study. The relationship was intense, while the gymnasium was something remote, obligatory – for me, not the real thing. When it came to actual learning, I was in a high school of one, alone with a master, Duerer, my tutor. This “instruction” was the most important and pleasurable part of my education, except for one other essential thing.

Sometime I would go on business trips with my father to buy and sell wood, and while he visited friends, I would sneak away to the magnet world of museums. There, in places like Berlin and Dresden, I devoured the history of art, which no longer resided in books but came to new life on the wall. This so transfixed me that the real world, already crumbling around me, seemed hard to exist. No matter how absurd it might seem to the rest of the world, my 17-year-old self knew exactly what it wanted to do. Though I never articulated it and certainly not to my businessman father, who saw me perpetuating his name in a very different way, in large letters over the sawmill, I wanted to be an artist.

But the real world had changed drastically around me. It had become a horror by many degrees and what remains, in the crucible of forgetting, is a confusing mix of parades and uniforms, swastikas and slogans, small injustices becoming large, and finally the inescapable reality and numbing brutality of war. The Weimar republic had given way to the Nazi regime, and one’s own life was no longer one’s own but at the service of the government. My classmates were drafted and began to fall one by one. I had a temporary reprieve when my service to the sawmill delayed my military deployment, but I was eventually sent to the Eastern Front. As a telegrapher, I had a more realistic sense of what was happening and the impending disaster for all. I was among those who managed to survive in the retreat from Stalingrad. Of the 33 members of my gymnasium class, only 8 returned to whatever life awaited in what became, literally overnight, East Germany.

Home was now inside the Russian zone as tanks rolled down the streets. In those years directly after the war, the sawmill became crucial to our survival. It had become not just the largest business and employer in town but one that reached well beyond the Harz. For years, our small factory provided wood reparations to Russia. Russian officers were stationed in our house. And I with my father – who under the strain of these circumstances suffered a heart attack – had the crushing responsibility of running the sawmill.

Art became more dream than reality. It was almost impossible to paint since there was little time and supplies. Activities were also under constant surveillance. Throughout those seven regimented years, my only solace was drawing in secret corners I would fashion. I would have left East Germany much sooner, as so many did before the Wall. However, I was reluctant to leave without my family. Only in 1952 did my father agree the situation was hopeless and would not change anytime soon. We devised a dangerous but successful plan of escape across the border, leaving everything behind in the hope of a better future and what, whatever its limitations, might be called a “normal life.”

It took some time before I was free to go out on my own, but I knew the first order of business was my long postponed art education. In 1956, I set myself up in Augsburg. I was accepted into the Art Academy in Munich even with all the new work to replace what I had left behind and my older age, 34. More than ready to make the most of my late start, I labored for over two years to catch up. I was fortunate to have the sharp eye and astute criticism of Professor Kasper advance the high standards I now set for myself in the pursuit of life as an artist. This also meant making a living from art, which I did in Augsburg and elsewhere by painting murals, creating mosaics, and staining glass windows. I got a world of practical experience that I could apply to that elusive goal I had not lost sight of, becoming an artist.

This period in West Germany, 1953-1959, was the most important in my artistic development. It solidified my European roots, gave me a backbone of self-criticism and a practical sense of making art that would never leave me. It also gave me the newfound freedom to travel and explore and to enlarge my knowledge of modern that had been so constricted in East Germany. The turning point was a trip to Paris where I could stand in front of the art of Picasso, Leger, Matisse, Miro, the Cubist and Surrealist painters. It was a vast universe of art of my own time that I had missed out on and never imagined existed. The Modernists electrified me with their bold ideas and color; they jolted my artistic system alive and capitulated me into the mid-20th Century with a clearer direction for myself in it.

In 1959 the USA was a lively and colorful destination and the mecca of modern art. I was determined to go there. As a “displaced” East German, I could have a sponsor to qualify, as I had at least initially, to live where they lived, in this case, in the Twin Cities, the heart of the Midwest. Here, St Paul/Minneapolis, was the home of Walker Art Center, one of the premiere art institutions in the USA. Before boarding the train to my new life in Minnesota, I stepped into the Museum of Modern Art, which only solidified the fact that New York was always my real destination.

In St. Paul/Minnesota, even with no English and no record to speak of, I was able to move within six months from menial jobs in a children’s hospital to a good living in commercial art. Portfolio in hand, I was soon putting my drawing skills to good use doing illustrations, portraits, layouts for ads even ending up within two years as art director for Catholic Digest. But I still worked furiously at my own art, showing more and more in galleries in the Twin Cities, where the Director of the Walker Art Center, Martin Friedman, noticed it. Incredibly, he gave me my first one-man show in a museum and introduced me to an important guest at a social function, Richard Lindner, a émigré painter living in New York whom I much admired.

Well able to support myself with the additional satisfaction of teaching art at the St. Paul Art Center and Hamline University and with frequent exhibits with good reviews, I might have stayed in Minnesota forever. But there was always New York. In 1972, I was finally ready. I had made an American salary and lived like a European. I knew I had enough money to survive three or four years as an artist in New York and take my chance. Before I did, I needed to recharge my batteries in what became a six-month artistic pilgrimage through Europe and the second turning point in my professional development.

In the 1950s, my trip to Paris was all about the future: I stood in the temple of modern art and was converted. In the 1970s, my trip to Europe was all about the past and a spiritual journey in quite the opposite direction. I had long dreamed of seeing the cave paintings of Altamira, Spain, which was still open to viewers at that time. It was my most important destination. However prepared I felt to see what fellow artists could do some 14, 000 years B.C., there was no imagining the spiritual impact of the experience. Even with a tour guide, a group of perhaps 20 people and artificial illumination in the confines of a cave, there was an immediacy and presence in those paintings that astonished me. On impulse I lagged behind and remarkably, nobody missed me. I was alone with their existence, their immersion in their art, a spiritual kinship emanating over eons from those animal portraits magically impressed on the walls and ceiling around me. I was captivated by their presence until the next tour came.

My pilgrimage extended to France, England, and Italy where I could commune in the charged silence of museums and churches with the painters of the Early Renaissance that I loved most: Cimabue, Giovanni di Paolo, Sassetta, and Piero della Francesca. They had stripped form, composition, and color to the essentials, filling me with new artistic purpose that I would bring to the formidable adventure of New York.

My entry into the New York art scene was like jumping into an immense pool of cold water. I plunged in anyway. I prepared a resume and portfolio to represent me and made the rounds. In short order found an inexpensive loft-studio in the old Soho of 1973.

There is something to be said for good timing because at exactly this moment galleries along Madison Avenue were preparing for what they called a New Talent Show. I was unexpectedly welcomed through the door on a surge of openness this invitation provided. Gimpel and Weitzenhoffer took me in. Never mind that I was 51, I was still new talent as John Russell of the New York Times pointed out in his review of the New Talent Show, choosing to reproduce my work along with his choice for sculpture. It was a solid beginning to my more than 20 years representation by Gimpel and Weitzenhoffer. Also soon after arriving in New York I formed another association that continues to this day. I met the novelist Diana Cavallo, an American, who spent many years in Italy and who became my wife.

From then on, my professional life became an intertwining of Europe and New York. Italian and German gallery owners and collectors seemed particularly drawn to my work and to my immense satisfaction, my German and American identities began to merge. I soon found myself in Germany twice a year for the Cologne Art Fair and for my frequent exhibits in German galleries: Heseler in Munich, Rehklau in Augsburg, and Stolz in Cologne among others. Perhaps the most significant example of my fused German/American identity was a joint show in 1979 with the Goethe House, New York offering a large retrospective show on Fifth Avenue, while only two blocks away Gimpel and Weitzenhoffer featured a one-man show of my new work.

Just about that time, a curator, Wolfgang Horn from the Kunsthalle in Nuremberg was strolling down Madison Avenue and saw my paintings in the window. This casual event led to a lifelong association between that city and me. In 1981, Director Curt Heigl of Kunsthalle, Nuremberg gave me the most extensive retrospective show of my life. Soon thereafter a Nuremberg Gallery, Galerie Bode, became the leading representative of my work in Germany and is to this day. My most recent exhibit, the 2004 retrospective show of my work in Neumarkt is a result of the collaboration of Galerie Bode of Nuremberg and Galerie Herrmann of Neumarkt.

My studio is still the center of my life and still in the USA. I changed studios only twice since my SoHo days. In 1984, I left Broome and Crosby Street to move further downtown, below City Hall, to the old Broadway between St. Paul’s Chapel and Trinity Church. I lived and worked there for almost 15 years. The World Trade Center was only a block away and walks along the Esplanade were part of my everyday. I would have never left, but in 1999, it became more convenient to move to Philadelphia, my wife’s home city where she taught at the University of Pennsylvania.

Little did I dream my happy days and beautiful studio/loft on Broadway would be recast after 2001. It would always be tied to the site and catastrophe of 9/11, forever in the shade of Ground Zero. But history, perhaps in my case more than most, played a leading role in my life story. I have lived long enough to encompass in my lifetime the Weimar Republic, the Nazi years, Communist East Germany, the fledgling West German Republic, and the USA before and after 9/11. It has been a hard, tempestuous, full, rich, sad and happy life – perhaps, even that, like most.

###

.jpeg)

.png)